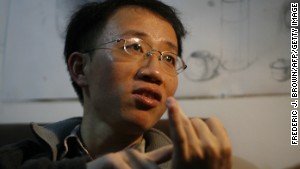

Joshua Wong, 17, is the founder of pro-democracy student group Scholarism. In 2012, he led as many as 120,000 people in a protest that overturned a pro-Communist school curriculum in Hong Kong.

Hong Kong (CNN) -- He's one of the fieriest political activists in Hong Kong — he's been called an "extremist" by China's state-run media — and he's not even old enough to drive.

Meet 17-year-old Joshua Wong, a skinny, bespectacled teen whose meager physical frame belies the ferocity of his politics. Over the last two years, the student has built a pro-democracy youth movement in Hong Kong that one veteran Chinese dissident says is just as significant as the student protests at Tiananmen, 25 years ago.

Echoing the young campaigners who flooded Beijing's central square in 1989, the teen activist wants to ignite a wave of civil disobedience among Hong Kong's students. His goal? To pressure China into giving Hong Kong full universal suffrage.

Wong's movement builds on years of pent-up frustration in Hong Kong.

Now, Wong aims to ignite a wave of civil disobedience among Hong Kong's students to pressure China into giving the city full universal suffrage.

When the former colony of the United Kingdom was returned to Chinese rule in 1997, the two countries struck an agreement promising Hong Kong a "high degree of autonomy," including the democratic election of its own leader. But 17 years later, little resembling genuine democracy has materialized. China's latest proposal suggests Hong Kongers may vote for their next leader, but only if the candidates are approved by Beijing.

Wong is bent on fighting the proposal — and impatient to win.

"I don't think our battle is going to be very long," he tells CNN. "If you have the mentality that striving for democracy is a long, drawn-out war and you take it slowly, you will never achieve it.

"You have to see every battle as possibly the final battle — only then will you have the determination to fight."

Youth awakening

24-year-old Samuel Li is the former secretary general of the Hong Kong Federation of Students. "I have been in contact with activists in China," he told CNN last year. "They are really interested in social movements in Hong Kong."

Doubt him if you like, but the young activist already has a successful track record of opposition.

In 2011, Wong, then 15, became disgusted with a proposal to introduce patriotic, pro-Communist "National and Moral Education" into Hong Kong's public schools.

With the help of a few friends, Wong started a student protest group called Scholarism. The movement swelled beyond his wildest dreams: In September 2012, Scholarism successfully rallied 120,000 protesters — including 13 young hunger strikers — to occupy the Hong Kong government headquarters, forcing the city's beleaguered leaders to withdraw the proposed curriculum.

Yvonne Leung, 20, is the president of the Hong Kong University Students Union. "My main concern is to end one-party rule in China," she told CNN in June.

Chinese dissident Hu Jia has been under frequent house arrest for 11 years.

That was when Wong realized that Hong Kong's youth held significant power.

"Five years ago, it was inconceivable that Hong Kong students would care about politics at all," he says. "But there was an awakening when the national education issue happened. We all started to care about politics."

Asked what he considers to be the biggest threats to the city, he rattles them off: From declining press freedom as news outlets change their reporting to reflect a pro-Beijing slant, to "nepotism" as Beijing-friendly politicians win top posts, the 17-year-old student says Hong Kong is quickly becoming "no different than any other Chinese city under central administration."

That's why Wong has set his eyes on achieving universal suffrage. His group, which now has around 300 student members, has become one of the city's most vocal voices for democracy. And the kids are being taken seriously.

In June, Scholarism drafted a plan to reform Hong Kong's election system, which won the support of nearly one-third of voters in anunofficial citywide referendum.

In July, the group staged a mass sit-in which drew a warning from China's vice president not to disrupt the "stability" of the city. In the end, 511 people were briefly arrested.

This week, the group is mobilizing students to walk out of classes — a significant move in a city that reveres education — to send a pro-democracy message to Beijing.

The student strike has received widespread support. College administrators and faculty have pledged leniency on students who skip classes, and Hong Kong's largest teacher union has circulated a petition declaring "Don't let striking students stand alone."

China's reaction has been the opposite: Scholarism has been named a group of "extremists" in the mainland's state-run media. Wong also says he is mentioned by name in China's Blue Paper on National Security, which identifies internal threats to the stability of Communist Party rule.

But the teenage activist won't back down. "People should not be afraid of their government," he says, quoting the movie "V for Vendetta," "The government should be afraid of their people."

Hong Kong a "seed of fire" for China

Compared to activists in Hong Kong, activists in mainland China face a situation far more grim.

Few understand this better than veteran human rights activist Hu Jia, 41. A teenage participant in the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests, he remembers witnessing the carnage in the aftermath of Chinese government's crackdown.

"At the age of 15, it made me understand my responsibility and my mission in life," he tells CNN in a phone call from Beijing. "The crackdown made a clear cut between myself and the system."

Tiananmen protester: I was willing to die

Inspired to fight for change, in 2000 he worked to expose "AIDS villages" in central China, where unregulated blood trades were infecting entire rural towns with HIV. But he paid a price: authorities jailed him for three and a half years for "inciting subversion of state authority," then placed him under frequent house arrest, where he remains today.

Fear has been deeply rooted in our genes through the past 65 years," he says. "The majority of China's 1.3 billion people are not true citizens — most of the people are simply submissive."

That's why Hu thinks Hong Kong, with its relative freedom, is a perfect place for activists to spark a democracy movement that could sweep all of mainland China.

"You can form political parties in Hong Kong. You can publish books that are forbidden in mainland China. The media can criticize the central government and the chief executive of Hong Kong.

"Mainland China is a tinderbox that's been physically suppressed by the authorities, and Hong Kong is a seed of fire.

"The Communist Party is very scared of this tiny bit of land, because if true universal suffrage can blossom in Hong Kong, it is very likely true universal suffrage will end up happening in the mainland."

It's a dream that Wong acknowledges. "I can't say we students striving for democracy now will directly lead to universal suffrage in China," he says. "But at least, universal suffrage in Hong Kong could be a pilot for the people in Guangzhou, Shanghai, Beijing, and even the whole of China — it would let them know that a Chinese society under the rule of a Communist Party can still have a fair system."

Because of the high stakes involved with challenging China, Hu says Hong Kong's activists should prepare for the worst.

"Maybe the Chinese government will one day send troops onto the streets, or even tanks," Hu says, though adding the possibility of the military actually opening fire would be "very small."

More likely, says the elder activist, the Party might go after individuals like Wong himself.

"Joshua Wong could be arrested, or jailed," Hu tells CNN. "I hope he understands this will be a battle of resilience. It is not a fight, nor a skirmish, it is a true war, in terms of the length of time it involves, its complexity, and the potential sacrifice it might involve."

Taken from

No comments:

Post a Comment